Oluwagbemi Samuel Adeoti and Saravanamuthu Vigneswaran explain how iterative research informed drinking water delivery that meets and responds to community need.

Achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6.1 – universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water – is a critical global challenge. While developed nations generally meet water accessibility standards, sub-Saharan Africa struggles with significant deficits in basic water services, affecting more than 336 million people. Nigeria exemplifies these challenges, with more than 40 million Nigerians lacking access to improved water sources and nearly half of its water infrastructure assets being non-functional or failed. This poses a critical issue given Nigeria’s rapid population growth. Addressing these infrastructure failures and ensuring sustainability is crucial to achieving SDG 6.1 in Nigeria.

Why are infrastructure assets in Nigerian communities failing?

Water infrastructure, such as boreholes, often fail because of issues ranging from poor planning in the pre-construction phase to lack of maintenance post-construction. A systematic review conducted by Adeoti et al. (2023), published in Water Policy, the official journal of the World Water Council, identified 265 factors causing infrastructure asset failures based on the analysis of 15 studies. These factors were grouped into 52 distinct themes and categorised into technical, financial, environmental, social, political, and institutional factors.

The complexity of these multifaceted issues requires a comprehensive approach and framework to navigate. However, there is no such framework in Nigeria. Consequently, the authors proposed a sustainability framework for water infrastructure in Nigeria, encompassing all stages of water development.

Creating a framework for sustainable projects

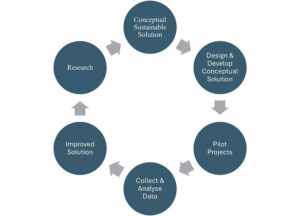

Developing a comprehensive framework requires an iterative research cycle based on a transdisciplinary research method. This method draws knowledge from various sectors, including industry experts, academia, government officials, and end users.

Through transdisciplinary PhD research, we have been dedicated to addressing the high failure rate of water infrastructure in Nigeria. We conduct our research by creating conceptual solutions, piloting them, collecting and analysing data, and continuously refining our approach. This iterative process helps us understand challenges, identify effective strategies, and build a sustainable framework for water infrastructure.

Our recent research (Adeoti et al. 2024), published in IWA’s journal Water Supply, challenges the prevalent assumption that state-level poverty metrics are reliable indicators of community water infrastructure and poverty conditions. The state-wide multi-dimensional poverty index often fails to capture the nuanced and localised challenges faced by individual communities. Precision mapping and comprehensive surveys are essential for identifying specific community needs and interrelated challenges.

Our recent research (Adeoti et al. 2024), published in IWA’s journal Water Supply, challenges the prevalent assumption that state-level poverty metrics are reliable indicators of community water infrastructure and poverty conditions. The state-wide multi-dimensional poverty index often fails to capture the nuanced and localised challenges faced by individual communities. Precision mapping and comprehensive surveys are essential for identifying specific community needs and interrelated challenges.

The study also examined borehole failure trajectories and classified states of functionality to mirror the actual conditions encountered on the ground, improving understanding of how boreholes transition from full operation to total failure and abandonment. The examination noted the lack of functionality monitoring and the absence of preventive maintenance as contributing factors. The study proposed the need for smart infrastructure for monitoring and data collection, enabling historical trend analysis and pre-emptive maintenance. Consequently, the study proposed that a holistic approach to water infrastructure sustainability must include mapping and constructing smart water infrastructure to ensure long-term sustainability.

What is mapping and why is it important?

As previously mentioned, more than 40 million Nigerians lack access to clean drinking water, yet the precise locations of these individuals remain unknown. Addressing people’s problems effectively requires understanding of where they live and the interrelated challenges they face. A mapping project aims to ascertain the locations of people suffering from extreme water poverty, identify the interrelated challenges they face, and gather necessary data to develop tailored and sustainable solutions for their communities.

A pilot project to test the feasibility of this mapping project was conducted across 1696 communities in three Nigerian states. The outcome demonstrated that mapping is essential, important, and achievable for creating tailored solutions that meet community needs and ensure longevity. The data on the mapped communities is kept up to date through communication with community caretakers identified during the initial mapping.

How smart water infrastructure can solve the problem

Smart Water Kiosk case study

Smart water infrastructure, leveraging Internet of Things (IoT) technology, enhances the efficiency and sustainability of water supply systems. By integrating sensors and smart meters, these systems collect extensive data, enabling proactive maintenance and strategic water resource management. This case study examines how the implementation of an initial Smart Water Kiosk (SWK) in a mapped community provided key insights, ultimately leading to the development of a more advanced mobile SWK.

Implementation and insights from the initial Smart Water Kiosk

The SWK was introduced as a pilot project to test the viability of smart water infrastructure. It was equipped with IoT devices capable of monitoring water flow, detecting leaks, and tracking the volume of water sold or dispensed. Over a three-year period (2021 to 2024), the SWK collected extensive data that proved crucial in assessing its effectiveness and guiding necessary adjustments.

Initially, the kiosk achieved a Self-Sustainability Rating (SSR) of 22%. However, uncoordinated aid efforts from another NGO, which installed a free-use water well within the community, led to an overlap of aid that drastically reduced this rating to zero. This overlap caused a significant drop in kiosk usage as residents opted for the free option, undermining their willingness to pay and threatening the kiosk’s sustainability. Consequently, water had to be provided for free to prevent abandonment. Despite this challenge, the kiosk eventually achieved a 100% Sustainability Rating (SR) through external support and maintained a high Reliability Rating (RR) of 97.1%, remaining operational for 1063 out of 1095 days.

Development of the mobile Smart Water Kiosk

The challenges and insights from the initial SWK informed the development of a mobile SWK, equipped with a water treatment plant. Designed to address the issue of aid overlap, the mobile kiosk offers flexibility, allowing it to be relocated when no longer needed or when similar aid initiatives arise in a community. This adaptability ensures that the infrastructure remains functional, sustainable, and effectively serves communities with genuine water needs, preventing redundancy and ensuring optimal resource utilisation.

Recommendations

The SWK case study demonstrates the significant potential of smart water infrastructure in addressing water poverty and infrastructure failures in Nigeria. The iterative process of designing, piloting, data collection, analysis, and redesign proved essential in developing resilient and sustainable solutions that cater to specific community needs. Mapping played a crucial role in this process, ensuring interventions were both effective and aligned with the realities faced by communities.

To build on these insights and ensure the long-term sustainability of water infrastructure projects, the following policy recommendations are proposed:

- Coordinate aid with centralised water management: Establish a centralised water asset database to prevent aid overlap and ensure efficient resource allocation. This system would help coordinate all water infrastructure projects, directing efforts towards communities with genuine needs, thereby avoiding redundancy and ensuring that contributions are complementary and sustainable.

- Adopt an iterative research and development approach: Implement an iterative research and development cycle, treating each water project as an ongoing pilot for innovation. This approach facilitates systematic data collection, identifies best practices, and allows continuous improvement. By refining smart water management practices based on real time data and community feedback, every project contributes valuable insights to enhance the design and implementation of future water infrastructure initiatives.

By learning from data and analysis, combined with lived experience, and a model that can adapt to community needs, this project has evolved, enabling it to be more flexible, sustainable and resilient.

The authors

Oluwagbemi Samuel Adeoti is a transdisciplinary PhD researcher at the University of Technology, Sydney, and CEO of Fairaction International

Saravanamuthu Vigneswaran is Emeritus Professor in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Technology, Sydney, and an IWA Distinguished Fellow

More information

For more details and access to the mapped communities, please visit:

https://target6.1map.management

doi.org/10.2166/ws.2024.127