The post Filling the skills gap appeared first on The Source.

]]>It is widely agreed that it will be a challenge to meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the 2030 deadline, and that huge financial and technological investments will be required to deliver SDG 6 – safe water and sanitation for all. Too frequently, however, discussions around capacity fail to recognise that progress will be dependent on fostering a sustainable and highly skilled workforce, without which the most generous financial commitment will be found wanting and destined for defeat.

Fundamental to the sector’s success is the recruitment, retention and training of a highly skilled and dedicated workforce, along with collaboration with a wide range of stakeholders and community engagement. Without investment in human capacity, increased financial expenditure is likely to result in wasted revenue through imprudent expenditure or unspent funds because of the lack of a skilled workforce. It is critical that the water and sanitation sector places focus on its organisational structures, the competencies that must be attained and developed, and the roles that will need to be created to future-proof growth and innovation in a changing world.

Skills targets

Of the 19 targets listed under SDG 6 in the Report of the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators, workforce capacity is barely referenced. In contrast, under SDG 3 to ‘Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages’, the health sector has a specific target to: ‘Substantially increase health financing and the recruitment, development, training and retention of the health workforce in developing countries, especially in least developed countries and small island developing States.’ And under SDG 4, to ‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’, the education sector has a target by 2030 to ‘… substantially increase the supply of qualified teachers, including through international cooperation for teacher training in developing countries, especially least developed countries and small island developing States’, and measures this by the proportion of teachers in schools with minimum required qualifications. These indicators have resulted in a clear emphasis on the workforce in these sectors and leveraged increased investment.

“Progress will be dependent on fostering a sustainable and highly skilled workforce”

In the case of health workers, the World Health Organization has an entire department focused on the Health Workforce. It supports countries with national human resource assessments, performs workforce related research to inform advocacy efforts, and provides guidelines for countries that want to take targeted action. Similarly, UNESCO’s Global report on teachers: What you need to know presents the challenges of the workforce capacity gap and provides guidance on how countries can tackle shortages effectively.

Securing leverage for the water sector workforce

Given this context, water and sanitation professionals ought to argue for the inclusion of a workforce target in future indicators, which would draw attention to the sector’s workforce capacity and open funding for further research, and maybe even increase budget availability to create new and much needed jobs. Such targets would also help align capacity development efforts, creating a common goal focused on investing in a sustainable local workforce to overcome the lack of coordination in capacity development identified in previous assessments, including IWA’s report An Avoidable Crisis: WASH Human resource capacity gaps in 15 developing economies, and the United States Agency for International Development’s Addressing the Human Resource Capacity Gaps in Rural Sanitation and Hygiene: Final Report.

Continuous transformation

While capacity development is a term that has its legacy in the colonial era, the term workforce resonates with local ownership. By focusing on the goal of achieving a sustainable, local workforce, capacity development moves from being a deliverable with an endgame to a continuous and transformative process.

Aligning capacity development and human resource development

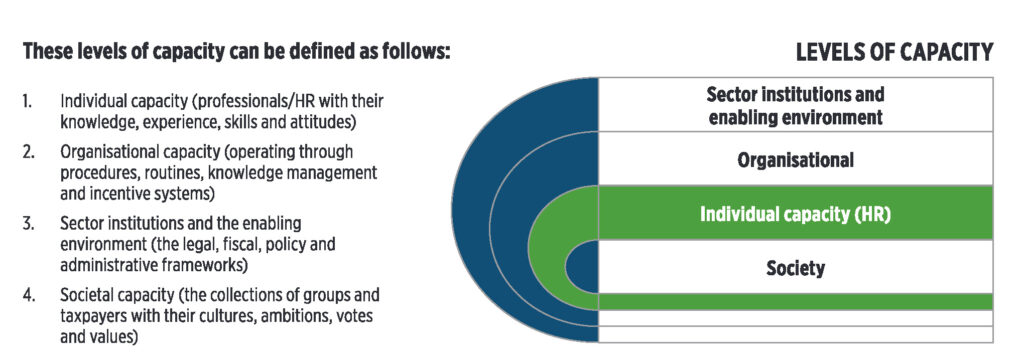

Implementing an intervention does not automatically ensure its effective application on the job, especially if the necessary organisational support – or perhaps even the availability of jobs – is lacking. This underscores the necessity of a holistic approach to capacity development to cultivate a sustainable, interconnected water and sanitation sector.

Capacity development principles

Within capacity development efforts there are still persistent challenges. Many relate to the failure to recognise the unique interests, needs and preferences of audiences. Capacity assessments in the water, sanitation, and hygiene sectors still report a mismatch between supply and demand, where supply focuses on the offer rather than soliciting what the audiences need. There continues to be an overemphasis on training, which neglects other ways of learning. Some capacity development interventions are still based on a one-size-fits-all approach and, in some cases, unidirectional learning is still practiced. The workload or time that participants have to attend classes or apply learning is also often not considered. Many capacity development efforts lack a comprehensive strategy (also referred to as a capacity development design) and fail to monitor and evaluate effective capacity development.

“The term workforce resonates with local ownership”

So, in addition to an emphasis on a sustainable workforce as the outcome of capacity development, and the adoption of a holistic approach that addresses multiple levels of capacity, there is a need for capacity development efforts to follow capacity development principles, such as:

Time and application: Allowing sufficient time for learning and providing opportunities for participants to apply their knowledge in their work, while considering local governance, mandates and roles to minimise disruption and extra workload.

Tailored solutions: Recognising the unique interests, needs, and approaches of different target audiences and developing customised capacity development activities that align with specific requirements, incorporating diverse learning methods, such as peer-to-peer interactions, virtual tours, mentoring, communities of practice, and working groups.

Engage specialists: Involving practitioners and experts in the design and implementation of capacity development programmes, ensuring a comprehensive design that considers different audiences, learning methods, and impact measurements.

Inclusive learning environment: Valuing participants’ input and expertise to create an inclusive and collaborative learning environment.

Evidence-based approach: Emphasising the importance of measuring impact and using effective capacity development practices. This data-driven approach enables continuous improvement and knowledge sharing.

Learning mindset: Fostering a culture of sharing experiences, success stories, failures and lessons learned, to encourage ongoing learning and adaptation.

By embracing these guiding principles, stakeholders involved in capacity development can address common errors and enhance the effectiveness of interventions in the water, sanitation and hygiene sectors. The ultimate goal of capacity development is to develop a sustainable workforce capable of performing functions, delivering services, and promoting sustainable development. The desired outcome of each capacity development intervention should be to contribute to this wider goal.

If we can agree that this is the case, push for the workforce to be embedded in post-SDG 6 targets, align capacity development with human resource development, think holistically about capacity development, and embrace guiding principles, we can address the effectiveness of our contributions, improve our coordination, and even increase investment in a sustainable water and sanitation workforce. •

More information

- un.org/content/documents/11803Official-List-of-Proposed-SDG-Indicators.pdf

- who.int/teams/health-workforce/health-workforce-development

- unesco.org/en/articles/global-report-teachers-what-you-need-know

- IWA (2014) An Avoidable Crisis: WASH Human resource capacity gaps in 15 developing economies, iwa-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/1422745887-an-avoidable-crisis-wash-gaps.pdf

- USAID (2023) Addressing the Human Resource Capacity Gaps in Rural Sanitation and Hygiene: Final Report, Washington, DC, USAID Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Partnerships and Learning for Sustainability (WASHPaLS) #2 Activity

- Lincklaen Arriëns, W.; Wehn de Montalvo, U.; (2013) ‘Exploring Water Leadership,’ Water Policy 15 (S2): 15–41. doi.org/10.2166/wp.2013.010

- Danquah, J.; Crocco, O.; Mahmud, Q.; Rehan, M.; Rizvi, L; (2022) ‘Connecting concepts: bridging the gap between capacity development and human resource development,’ Human Resource Development International. 26. 1-18. doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2022.2108992

The author: Kirsten de Vette is an independent consultant and facilitator specialising in capacity development, knowledge management and learning, and stakeholder engagement in the water, sanitation, and hygiene sectors

The post Filling the skills gap appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post Danube invests in human capacity for cleaner water appeared first on The Source.

]]>New partnerships and personnel appointments have given utilities a bigger role in the management of the river Danube. By James Workman

It is not the deepest, steepest, longest or strongest but from its source in Germany’s Black Forest town of Donaueschingen, to its mouth in Romania’s free port of Sulina on the Black Sea, the Danube is by far the world’s most politically complex river, traversing ten countries, and with tributaries, draining nine more. Geostrategic forces have shaped borders since ancient Rome. But as urbanisation has brought new threats, today’s Danube is primarily an urban river that runs through or past 98 cities, including four major capitals.

Yet for centuries, the river sparked rivalries rather than trust. Each city along the river acted more or less alone, despite sharing a common resource. They worked in isolation within the same country, let alone across national borders; and this worsened after World War II with divisions into the Eastern European bloc.

All too often, cities diverted upstream currents like an intake pipe for use, then disposed of urban waste (treated or untreated) back downstream as a natural sewer. But this changed starting in 1993, after the Iron Curtain fell, when a new utility alliance set out to replenish the Danube.

“There is no more basic interest than the common interest of ensuring good clean water supply,” says Walter Kling, Secretary General, International Association of Water Supply Companies in the Danube River Catchment Area, or IAWD. “Water is a common link between the people of the river basin and having mechanisms to ensure cooperation on this important resource between cities and municipalities ensures that trust and good relations exists.”

Riparian cities now seek a more assertive role, coordinating efforts through IAWD to address the double challenge: providing clean water and wastewater services, while meeting the EU’s rigorous environmental obligations or “Acquis Communautaire.”

Rather than emerge in a vacuum, this effort builds upon past diplomatic efforts. National delegations formed the cooperative Danube River Protection Convention, and set up the international commission (ICPDR) to implement it. Yet the international alliance lacked the energetic involvement by city utilities both upstream and down. Few platforms helped water professionals share experience, best practices, and coordination within its larger scope.

“The voice of water utilities is important in helping shape decisions that affect the waters of the Danube region, and that voice needs to be strong and well organised,” says Kling. “Water utilities have begun to realise that the security of a safe clean supply of water is dependent upon them actively working together to both technically use the best management and operational techniques but also to ensure that river basin cooperation is happening to protect and restore water systems.”

IAWD has strengthened the voice of the utility operators and owners in the debate about river management, says Kling. Water provision and wastewater treatment are recognised as core elements of responsible river basin management. More recent measures seek to bolster cooperation among water professionals and enhance the region’s utility sector. IAWD and the World Bank leveraged €9.5 million in funds from Austria to launch the Danube Water Program to provide analysis, share knowledge, develop capacity and unlock grants.

More recently, IAWD signed a memorandum of understanding with the International Water Association to build capacity, engage national entities, and open up more learning and networking opportunities for Young Water Professionals in the region. At a meeting in Prague on 22 September, the IWA announced that IAWD has taken on the role of Coordinator of the Danube-Black Sea Region.

And personnel choices reflect these policy priorities. Kling is Deputy Managing Director of Vienna Waterworks; IAWD current president Vladimir Tausanovic used to run the Belgrade Waterworks; and Philip Weller (formerly at ICPDR) runs the IAWD Technical Secretariat, which is implementing the Danube Water Program under the guidelines of “Smart Policies, Strong Utilities and Sustainable Services.”

Like the physical river itself, information, funds and capacity building efforts tend to flow downstream. Indeed, IAWD has collected performance indicators and metrics for success, and while it seeks to harmonise the basin as a whole, there is greater demand in lower elevation cities. The institution was set up to address exactly those challenges for water services, to help overcome the economic differences, with Western members supporting their Eastern colleagues.

“Some worried about cooperation between the World Bank and IAWD, given the disparate scales. But Weller has found it a “highly practical marriage.” The high-level economic skills of the bank complement the on-the-ground technical competence of IAWD, and the differing skills and perspectives seem to fit well together.

EU accession has helped drive basin-wide efforts to improve water services, particularly wastewater treatment, says Kling. The problem is “that simply building wastewater treatment facilities does not necessarily guarantee good quality of water or effective operation.”

It remains a challenge to manage facilities in an economically sound and sustainable way.

IAWD offers a new model for riparian cities in other basins. Riparian stakeholders who value institutions within a basin’s ecological boundaries can support cooperation synergies. Indeed, Kling anticipates IWA’s role in a “third phase” of the Danube Water Program as being a “necessary evolution” that links urban utilities with hydropower, flood protection, and navigation.

The post Danube invests in human capacity for cleaner water appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post The truth of inconvenience: why disrupt water management in a time of universal water provision? appeared first on The Source.

]]>On 1 August 2015, Japan’s national water day, 32 households in a neighbourhood of Matsue city, near beautiful Lake Shinji, discovered they were without running water. Although the threat of earthquakes is very real in Japan–with about twenty earthquakes with a magnitude 7.0 or more on the Richter scale in the last decade–fortunately for these families this was just a staged exercise. The drill was organised so that citizens could experience the inconvenience of water supply disruption and be prepared to react to its potential risks.

Matsue City Waterworks Bureau’s emergency response drill goes one step further than conventional training. With prior consent from residents, the Bureau staff visited houses in the morning to shut off water. Meanwhile, a water truck arrived to the neighbourhood to provide water needed for their daily life. For some two and a half hours, residents voluntarily experienced the hardships of a hot summer day with a dry tap.

The Bureau stated there were two reasons for conducting this drill. Firstly, the simulation trainings have become formalistic and started to lose substance and impact. Trainings are conducted every year, but there were doubts about whether participants actually understood what it actually meant to have no access to drinking water and sanitation services.

Secondly, the exercise was conducted as part of a public communication strategy. The major construction of waterworks systems in Japan was undertaken some four decades ago. Upgrading this ageing infrastructure to meet new earthquake-proof standards requires investment, which often translates into an increase in water tariffs. The exercise is a good way to get stakeholder buy-in for the investment.

Importantly, the drill was followed by a meeting with the neighbourhood’s residents to exchange opinions about the exercise with the Bureau staff. Participants commented, for instance, that despite knowing about the drill, they’d still unconsciously turned on the tap, and that further assistance should be available for elderly people.

Although small in scale, this initiative is a step towards increasing social awareness of the challenges facing water services systems in an era marked by more severe climate change impacts. It also offers powerful lessons to take forward.

First, it reveals an inconvenient truth that needs to be understood: shocks and disruptions to our water services systems are inevitable. Water services systems operate in an environment where risks are growing. No matter how much our water systems improve, no one can guarantee that we won’t find ourselves left without tap water.

As a Japanese proverb goes, natural disasters occur when you least expect them. Accepting that risks of disruption will never be mitigated entirely brings us to another powerful realisation. One of the key aspects of resilience is to build responsiveness on the part of society. As this exercise revealed, if local communities learn to organise and self-help when an extreme event or disaster, the damage could be significantly reduced and the community becomes more resilient.

The IWA is working to embed resilience and community participation in the daily working of water services providers. One initiative aims to identify water services regulation strategies that address different dimensions of resilience. Another, IWA’s project on public participation in the regulation of urban water services, looks into the often-controversial question of tariff-setting. The premise being that better processes can contribute to good decision-making and improve trust among citizens.

Ultimately, this contributes to the effectiveness of such decisions and the sustainability of the whole system, creating a virtuous circle of resilience that can prepare communities for a more unpredictable future.

The role of regulation and regulators in building resilience towards a sustainable, water-wise world, was the focus of the last International Water Regulators Forum (IWRF) and will be further discussed as cornerstone of their role in achieving the SDGs in the upcoming 4thIWRF on November 14th 2017 alongside the next IWA Water and Development Congress in Buenos Aires.

If you have an interest in any aspect of water policy and regulation, join us to share knowledge and network with regulators from around the world at the International Water Regulators Forum.

The post The truth of inconvenience: why disrupt water management in a time of universal water provision? appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post Flooding threatening 4.2 million people on Caribbean and Pacific islands appeared first on The Source.

]]>In addition to coastal erosion, rising sea levels are expected to negatively impact economic output and employment and could aggravate inflation and cause an increase in government debt, according to the study, A Blue Urban Agenda: Adapting to Climate Change in the Coastal Cities of Caribbean and Pacific Small Island Developing States.

“Caribbean and Pacific coastal cities are on the frontlines of climate change,” said Michael Donovan, Senior Urban Specialist at the IDB, and co-author of the study. “It is critical to adapt and improve the resilience of cities in coastal zones, especially those experiencing rapid urbanisation. Mayors in port cities across the globe could benefit from the policies that Small Island Developing States are developing as their governments respond to coastal transformation.”

One out of five residents of Caribbean and Pacific SIDS live in low-elevation coastal zones, which are defined as areas with elevations less than 10 metres above sea level. This is most extreme in The Bahamas and the Republic of the Marshall Islands, where over 80 percent of the population live at low elevations.

The international community has begun responding to the challenge. The study reviews aid and private sector flows totalling US$55.6 billion provided to Caribbean and Pacific SIDS over a 20-year period ending in 2015 and found that increasing emphasis has recently been placed on comprehensive programmes for strengthening coastal city resiliency.

“The donor community and Small Island Developing States have been innovative in their efforts to solve this problem in the context of what is known as the ‘Blue Urban Agenda’,” said Michelle Mycoo, lead author from the University of West Indies, St. Augustine, located in Trinidad and Tobago. “The challenge facing SIDS government officials is investing in protection of their highly vulnerable coastal cities before the damage occurs.”

As you can see this is how playing poker online works if you are playing poker in a poker room such as this Americas Cardroom or http://www.americascardroom.org/americascardroom.com

The study reviewed the efforts made by Caribbean and Pacific SIDS to implement adaptation strategies aimed at reducing vulnerability and enhancing sustainability. It shows an increasing emphasis on urban governance and institutional capacity building within city planning agencies.

The post Flooding threatening 4.2 million people on Caribbean and Pacific islands appeared first on The Source.

]]>