The post New WMO report provides global drought monitoring insights appeared first on The Source.

]]>Titled ‘Drought Impact Monitoring: Baseline Review of Practices’ and released under the banner of the Integrated Drought Management Programme (IDMP) – a joint initiative of the WMO and the Global Water Partnership (GWP) – the report presents a global overview of current drought impact monitoring practices, highlighting case studies and identifying examples of good practice and enabling environments that support effective monitoring.

The report provides operational guidelines to help countries establish or refine their drought monitoring systems and encourages cross-sector collaboration, open databases and tools to improve data accessibility, and tailored systems that can be adapted to local needs.

The post New WMO report provides global drought monitoring insights appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post New UNCCD report warns of climate-induced aridity crisis appeared first on The Source.

]]>The report, ‘The Global Threat of Drying Lands: Regional and global aridity trends and future projections’, states that 77.6% of Earth’s land experienced drier conditions during the three decades leading up to 2020 compared to the previous 30-year period.

Over this period, drylands expanded by about 4.3 million km2 – an area nearly a third larger than India – covering 40.6% of all land on Earth (excluding Antarctica). It also finds that in recent decades 7.6% of global land – an area larger than Canada – was pushed across aridity thresholds (i.e. from non-drylands to drylands, or from less arid dryland classes to more arid classes). Most of the areas that have transitioned were previously humid landscapes that have now become drylands, with researchers warning that failure to curb greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) would result in another 3% of the world’s humid areas becoming drylands by the end of this century.

Launching the report, UNCCD Executive Secretary Ibrahim Thiaw said: “This analysis finally dispels an uncertainty that has long surrounded global drying trends. For the first time, the aridity crisis has been documented with scientific clarity, revealing an existential threat affecting billions around the globe.

“Unlike droughts – temporary periods of low rainfall – aridity represents a permanent, unrelenting transformation. Droughts end. When an area’s climate becomes drier, however, the ability to return to previous conditions is lost. The drier climates now affecting vast lands across the globe will not return to how they were, and this change is redefining life on Earth.”

As the planet continues to warm, the report’s worst-case scenario projections suggest up to 5 billion people could live in drylands by the end of the century, with dire implications for the wellbeing of people and the environment.

The report’s authors provide a comprehensive roadmap for tackling aridity, emphasising mitigation and adaptation, and recommending a strengthening of aridity monitoring, improved land use practices, investments in water efficiency, resilience building, and the development of international frameworks for improved cooperation.

The post New UNCCD report warns of climate-induced aridity crisis appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post The systemic switch for surviving drought appeared first on The Source.

]]>Highlighting drought as an “existential threat to many parts of the world”, the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, in its ‘GAR Special Report on Drought 2021’, seeks to raise awareness of the risk posed by the periodic lack of water. “The risks that drought poses to communities, ecosystems and economies are much larger and more profound than can be measured,” it states.

The aim of the report is to help move forward thinking and action, offering “a clear step forward” in building awareness of the characteristics of drought. The main thrust of the report is to call for a systemic approach and for adaptive governance. “It builds the case for a new approach to drought risk management,” it states.

The report illustrates the systemic nature of drought risks with examples such as the role of physical feedback loops where, for example, droughts in Europe in spring are connected to a higher probability of heatwaves in summer. In the wider agroclimatic system, a heatwave during an important crop growth stage can lead to crop failure and nutrient losses, with further rapid and irreversible changes potentially occurring as a result.

Drought is a concern because of its broad impacts, with most of these being indirect ones. “They cascade through economies and communities and continue over time, dwarfing direct losses,” the report notes. So, the systemic aspects also include cascading impacts such as loss of crops and spikes in prices and resulting social vulnerabilities, with individuals, communities and even nations potentially seeing their economic strength reduced.

Climate change is further complicating the picture. An effective response to the threat posed by drought requires management and governance that is designed to adapt over time. The report sets out what are described as “a basic set of key actions” both to develop the evidence base that is needed and to inform and support improvements at all levels – from international agencies right down to the community level.

Key actions

One important area of action is to invest in drought risk identification and mapping. Here, the report identifies a need to map decision making arrangements and stakeholders. Given the importance of action at the local level, this should include the public and private sectors, civil society and the science and technology community – as a step towards them taking part in drought risk management, design, planning and implementation.

Resilience-based approaches need to be mainstreamed, so another important area is for shared visions to be co-developed, with systematic coordination across actors, sectors and levels of governance going beyond ad hoc projects.

Actions on mechanisms for offering social protection should include conducting impact-based drought risk assessments focused on vulnerable communities in national and sector development planning and investment. There is also a need to ensure social accountability, for which action can include placing policy responsibility for drought risk reduction in a single unit with political and investment authority.

Finally, there is a need to promote coherence across implementation of the various international initiatives, such as the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal agenda and the Paris Agreement, in connection with drought risk reduction. This should include piloting and implementing innovative financial strategies to upgrade settlements, and promoting benefits of technology and efficiency of water, energy and land use.

The path to change

These are the key actions needed. The bigger challenge is of how to see these actions progressed and implemented.

The report summarises the systemic nature of drought risk as follows: “Increasingly globally networked risks, local imbalances, the resulting contagion of cascading risks and ensuing actions are overwhelming traditional approaches to drought risk management. Systemic innovation strategies for equitably addressing such multi-scaled risks are fundamentally different from regular innovation strategies, in that they are founded on notions of complexity, ambiguity and diversity to manage present risks and adapt and thrive as new risks emerge.”

This points to the need for a change of approach if the key actions are indeed to see progress. The report continues: “Instead of targeting only one outcome (e.g., a high crop yield), systems-based management aims at the capacity of systems and people to be able to imagine, adapt and co-produce a sustainable and equitable future.”

The report notes that decisions are often not based solely on weighing up costs and benefits but on experience, culture and values. The authors see this as the key to action.

“An immediate and critical need is to craft new narratives of measures of human well-being and interaction with natural systems, within and among countries in increasingly drought-prone, drought-emergent and water-scarce seasons and regions,” the report states.

Drought action as a driver for sustainability

In fact, the authors see that lessons from how the world approaches drought can be put to use in other areas. “Droughts provide a useful analogue and practical experience for a much wider suite of complex and growing risks – including those posed by climate change,” the report notes. The value comes from the combination of the uncertain nature of projected impacts and the need for a flexible approach.

The authors see that embracing a systemic approach can support a wider shift to sustainability.

“A significant challenge in the development of pathways for living sustainably with nature and with increasingly complex drought-related risks will be in guiding evolution of financial and economic systems towards a globally sustainable economy,” the report states, continuing: “This will involve steering away from the current limited paradigm of economic growth and drawing upon diverse value bases and sources, including indigenous and local knowledge.”

This presents a crucial role for the new narratives: “Such narratives would show the limits of current systems and business-as-usual actions in reducing risks into the future, and articulate shared values and opportunities for realizing the benefits and dividends of adaptive governance of systemic risks for global, national and local communities.”

The post The systemic switch for surviving drought appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post Why efficiency programmes are the best strategy for water security appeared first on The Source.

]]>The world is watching with sympathetic alarm as Cape Town’s water crisis deepens.

As of 1 February 2018, fewer than 100 days of water remain to serve a growing metropolitan population of 4.3 million. The shortage, largely due to rapid population increases of 79 percent in only 23 years, hints at future urban shortages looming from Tehran to São Paolo to Bangalore, all experiencing the same phenomenal growth and thus also facing the prospect of running out of water within a frighteningly short timeframe.

What should they do? During past water crises, city leaders typically beg their citizens to conserve water, anticipating that they will very soon have to take more drastic steps, such as rationing access or even outright shutoff. As the city falls deeper into water deficit, it concurrently races to increase supplies as quickly as possible, rushing through contracts for dams, diversions, wellfields and desalination plants to match the burgeoning demand. But in reality the timetable for developing meaningful new supply can take decades, not months.

There is, however, a third way: investing in water efficiency.

A water utility’s direct investments–installing water efficient plumbing, appliances, equipment and demand-side programmes–can yield tangible results. Every cubic metre of ‘old water savings’ translates into a unit’s ‘new water supplies’ that can be delivered immediately to city residents impacted by shortages. The soft and light efficiency investments also make the city’s long-term delivery system more resilient, at a far lower cost, than building heavy new supply-side infrastructure.

This ‘third way’ buys time, as Cape Town can learn from a place that already ran out of water. Nestled between two mountains southwest of Chattanooga, Tennessee, the tiny town of Orme was once a humming coal-mining community. In 2007, its well ran dry, with no other water supply available. The emergency response was to bring in water in a fire truck from a neighbouring town; that provided Orme’s residents with water for three hours a day. In 2008, volunteers from the plumbing industry replaced all the old fixtures in the town, installing in every home and business new water efficient toilets, showerheads, and taps. These efforts successfully quadrupled the meagre three-hour-per-day supply to twelve.

To be sure, Orme is a small town that offers a simple example. Yet metre for metre its proven solution can be quickly replicated and scaled up for much larger cities. Water saved through plumbing retrofits can then be made available to other residents to ease the shortage. Properly financed, water efficiency programmes can save a considerable amount of water, equalling or even surpassing over time the amount of water filling a newly constructed reservoir. But the important point is this: on the basis of cubic metres gained, water efficiency programme investments are much cleaner, cheaper, faster and fairer than building new supplies.

Australia learned this lesson during its 10-year Millennium Drought. Building new dams would have cost US$1,370 per Megaliter (/Ml) of water delivered. By contrast, the same Ml could be added by plugging leaks in the network at a cost of only US$365/ Ml and the country gained additional supplies by replacing high flow plumbing fixtures for just US$454/ Ml, less than a third of the cost of developing new supply.

Los Angeles has reaped even higher gains from water efficiency. The most affordable desalination plant would have cost the city US$1,216/Ml so the city turned to direct investments in water efficiency retrofit programmes that cost as little as US$41/Ml, less than 4 percent of the cost of the desalination plant compared per Ml. Even recycled water can be produced and delivered in Los Angeles for as little as US$487/Ml.

Money matters most for tight urban budgets. Yet beyond cost savings, and averting a catastrophic shortage crisis, water efficiency investments also provide long-term energy savings and spur economic development. A recent Alliance for Water Efficiency study found that direct national investments in water efficiency programmes can generate economic benefits up to 2.8 times the value of the original direct investments and boost Gross Domestic Product up to 1.5 times the original investments. They also generate demand for skilled labour, creating 12,000-26,000 jobs for every US$1 billion invested–a politically popular outcome that helps ease the transition.

Water efficiency can also minimise a rise in the water tariff that would otherwise have risen to cover expensive new supply and treatment capacity. Studies show that tariffs are lower when long-term water conservation programmes have been implemented that keep demand level even as population increases. A report in Westminster, Colorado documents that their tariff would have been nearly twice as high if 25 years of water efficiency investments had not been made to avoid these more expensive capacity increases.

Investing in efficiency makes sense for any water utility struggling with growing consumer demand, preferably before the shortage starts. But even during a crisis, cities can implement efficiency programmes much faster than constructing new reservoir supply, at lower cost, and with greater resiliency.

As reservoirs empty and aquifers dwindle, it is painful enough–and rarely successful–to ask consumers to voluntarily change behaviour overnight. A truly successful utility will match customer outreach with direct utility investments using fixtures, which are as efficient as possible.

The post Why efficiency programmes are the best strategy for water security appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post IWMI brings in new leadership appeared first on The Source.

]]>The International Water Management Institute has appointed two new executives with broad experience in the conservation and use of transboundary rivers.

Claudia W. Sadoff arrived in October 2017 to serve as Director General of the Colombo, Sri Lanka-based scientific research organisation. She brings to the post three decades of building a global network of development partners, and distinguished experience as a global researcher and development practitioner.

“Through sustained and strategic efforts, Dr Sadoff has made a major contribution toward the achievement of global water security,” said Donald Blackmore, Chair of the Institute’s Board of Governors.

Sadoff previously led the World Bank’s Water Security and Integrated Water Resources Management division where she engaged with development experts and policy makers at the highest levels addressing challenges from climate adaptation to drought and flood response, and transboundary river basin management. Most recently, she has led major studies on water security in the Middle East and on water management in fragile and conflict-affected states.

“IWMI is uniquely well placed to champion the cause of improved water management worldwide, and I look forward to offering my knowledge, experience and energy in support of the Institute’s mission to deliver evidence-based solutions for water management,” Sadoff said.

To that end, one of her first decisions was to bring on board Mark Smith as IWMI’s new Deputy Director General (Research for Development), starting in May 2018. Smith comes from 10 years serving as Director of the Global Water Programme at IUCN, where he led major, cross-sector initiatives–BRIDGE, SUSTAIN-Africa and WISE-UP to Climate–at the interface of water resources, development, conservation, food security, governance and resilience.

As Deputy Director General, Smith will lead IWMI’s science agenda to address global development challenges for water security and natural resources management. His responsibilities will include assuring research quality and relevance; leading the identification and prioritisation of innovative research areas; and ensuring that IMWI’s work contributes effectively to the SDGs, the global climate agenda, and CGIAR’s Strategy and Results Framework.

The post IWMI brings in new leadership appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post IWA and World Bank launch innovative groundwater report appeared first on The Source.

]]>The Forum addressed one of the region’s most ecologically complex and politically sensitive issues, and elevated groundwater on the foreign policy front, leaving India and its neighbours open to multilateral engagements.

“All who came, did so with an open mind to engage and learn from each other,” said Sushmita Mandal, IWA’s India Programme Manager and one of the report’s editors. “It was an opportunity that made the issue of groundwater visible. The timing was critical, as the region was reeling under the impacts of drought, poor monsoons, and improper management of available resources in the summer of 2016.”

How reliant is South Asia? Consider that India, Pakistan and Bangladesh together pump almost half of the world’s groundwater used for irrigation. Groundwater supports the livelihoods of 60-80 percent of the population, and has, as during the Green Revolution, helped lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty.

Yet groundwater has also been undervalued and overexploited. Excessive, intensive, and unregulated use has resulted in dry wells and declining water tables. Depletion itself can be fixed. But related land subsidence, saline intrusion, or contamination from arsenic, fluoride, sewage, effluent and chemicals may be too costly or impossible to reverse.

The 100-page synthesis is comprehensive, but more valuable than its words are the unique process and diverse people who spoke them. In a thirsty region often known for quarrelling over shared water resources and transboundary basins, the gathering was marked by mutual respect and active engagement.

The Forum provided the first transnational meeting of its kind, a platform to address groundwater management and governance. By generating broad consensus that there is scope to engage, interact and learn from each other, the new report provides a stable foundation for the next.

The post IWA and World Bank launch innovative groundwater report appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post Cape Town begins site preparation for desalination plant appeared first on The Source.

]]>Seven projects have been earmarked as part of the first phase of the city’s Additional Water Supply Programme. These are the Monwabisi, Strandfontein, V&A Waterfront, and the Cape Town Harbour desalination plants; the Atlantis and Cape Flats Aquifer projects; and the Zandvliet water-recycling project, which will collectively produce an additional 196 million litres per day between February and July 2018.

“Being mindful of the potential financial impact on water users, the city has worked really hard to see what existing budget it has available by making tough choices and reprioritise spending to boost drought mitigation initiatives,” said Councillor Xanthea Limberg, the City’s Mayoral Committee Member for Informal Settlements, Water and Waste Services and Energy. “It is anticipated that the Monwabisi plant will produce a total of 7 million litres of drinking water per day which will be fed into the water reticulation system.”

A nine-week construction period is planned for the completion of the first phase, comprising of two million litres. The first drinking water generated by the desalination plant is expected to be fed into the reticulation system by March 2018 with the second phase of 5 million litres to follow on after a further nine weeks.

All plants will comply with national legislation, which also provides for some fast-track measures for disaster relief projects such as the city’s emergency projects.

“The plant is intended to operate for a period of two years, based on a service agreement in which the city has agreed to buy water from the service provider, Water Solutions Proxa JV,” added Limberg. “The value of the tenders for the establishment and operation of the desalination plant at Monwabisi for a period of 24 months is R260 million (US$20.6 million).”

The post Cape Town begins site preparation for desalination plant appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post Why Latin America’s hidden reserves are at risk appeared first on The Source.

]]>By Stephen Foster and Ricardo Hirata*

With 80 percent of Latin America’s population living in cities, municipal demands for a reliable clean water supply have escalated. The combination of drought reliability, low well construction costs and increasingly polluted rivers has led to greater dependence on groundwater. UN-Habitat’s data tracking system lacks specific data, but in recent years many cities have come to depend heavily on this invisible resource: in Brazil alone, groundwater now supplies 53 percent of urban municipalities, amounting to a population of nearly 80 million.

But can urban aquifers cope with the pressures from rapid urbanisation?

For some cities–such as Lima, Merida, Natal, Ribeirão Preto and Belém–the urban centre is surrounded by high-yielding aquifers, allowing utilities to expand water production incrementally, and thus offer lower prices and higher service levels. Indeed, the complementary characteristics of groundwater storage and surface-water resources can be coordinated to enhance urban water-supply security greatly.

Unfortunately, many of today’s ‘conjunctive use’ practices only amount to a piecemeal coping strategy. Too often, water utilities construct new wells for base-load supply in newly urbanised peripheral suburbs, while overlooking the opportunity to use groundwater across an entire urban area to provide greater water-supply security during drought. In the longer term, this is unacceptable.

Urban water users have widely turned to groundwater for private in-situ supply, to improve their own water-supply security. But official statistics often obscure this reality. For example São Paulo states that less than 2 percent of public water supply comes from groundwater, but during the recent water-supply crisis 12,000 private wells provided 865 Ml/d (24 percent of the total supply).

The underestimation causes serious financial complications. Private capital for tapping groundwater is first triggered in times of crisis, but once initial funds are sunk, a temporary coping strategy will persist. Multi-residential dwellings and commercial and industrial users will keep pumping groundwater, especially when doing so costs less than the mains water supply. Thus private groundwater use can have major implications for planning investment in municipal water infrastructure, and public administrations will require a critical assessment of private urban well-usage in order to formulate a balanced policy.

Private groundwater supplies are often more vulnerable to anthropogenic pollution or natural contamination than better engineered and monitored utility sources. But attempts to ban private groundwater use are normally futile, and it is more appropriate to seek ways to maximise its benefits whilst minimising the associated risks. One approach is to register commercial, industrial and large residential users, and charge for groundwater abstraction based on well pump capacity or by metering their sewer discharge. This will also allow advice on water-quality and health warnings to be issued, and if pollution is severe, the sources can be declared as unsuitable for potable use.

Unmanaged groundwater can pose various threats to cities. Urbanisation modifies the ‘groundwater cycle’ by increasing recharge. Yes, impermeable surfaces reduce infiltration but this is more than compensated by recharge from water-mains leakage, wastewater seepage, and storm-water ‘soakaways.’ There may also be major groundwater discharge as a result of flows to deep collector sewers and drains. Such modifications are in continuous evolution and can seriously reduce the resilience of urban infrastructure.

The threats vary with development stage and type of groundwater system involved. Rarely are groundwater resources within an urban area sufficient to satisfy the entire needs of larger cities. So unmanaged abstraction and depletion can result in serious risks of quasi-irreversible side effects, like land subsidence and damaged infrastructure, as for example in Mexico City.

Conversely, as cities evolve, groundwater pumping in central districts often declines, resulting in strong water-table rebound that can cause a different kind of threat, such as basement damage and flooding, malfunction of septic tanks and excessive inflows to deep collector sewers, as was experienced some years back in Buenos Aires.

Groundwater systems underlying cities represent the ‘ultimate sink’ for urban pollutants. Large-scale in-situ urban sanitation poses a groundwater quality hazard, especially as regards to nitrate, some synthetic hydrocarbons, and pharmaceutical and hormonal residues.

Except for very shallow and vulnerable aquifers, there is usually sufficient natural attenuation capacity to eliminate faecal pathogens from percolating wastewater. But the hazard increases markedly with inadequate well construction or poor septic management, which often occur in fast-growing anarchical cities. Thus consideration of groundwater quality should be incorporated into urban sanitation planning in Latin America. The level of nitrate loading will rise with population density served. Municipal water utilities usually try to handle the problem by dilution, but this requires a secure source of high-quality water, which can face absolute limitations.

To fill the ‘vacuum of responsibility’ for urban groundwater, local development decisions need to be closely coordinated among diverse organisations. These include water-resource agencies that authorise well drilling; utilities producing and distributing water supplies; municipalities building infrastructure and planning land use; and environmental and public health agencies installing sewerage and disposing of liquid effluents and solid waste. All of them must be bound by the need to protect the groundwater they share, and a more integrated approach can reduce the cost and improve the security of urban infrastructure.

The post Why Latin America’s hidden reserves are at risk appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post G7 countries can help farmers access data for building resilience appeared first on The Source.

]]>“There is an urgent need to take the data which is available globally and to translate it to the ground level,” Graziano da Silva said in remarks made during a G7 Agriculture Ministers meeting session entitled Empowering Farmers.

Farmers, especially smallholders and family farmers in developing countries, incur much of the impacts of climate change and other shocks including price volatility. This at a time when, for the first time in over a decade, estimates show that hunger is on the increase with 815 million people suffering from chronic undernourishment.

The FAO Director-General noted that building the resilience of farmers to extreme weather events linked to climate change, including droughts and floods, also requires making better data available to more people, especially those living in poor and often remote rural areas.

FAO is working with the World Meteorological Organization to better respond to climate variability and climate change on the basis of better and more readily accessible data. Some 75 countries mainly in Africa, and many Small Island Developing States, do not have the capacity to translate the weather data, including longer-term forecasts, into information for farmers.

Improved access to quality data plays a key role in combating hunger and poverty by providing farmers with vital information, including on access to food and other agricultural products. Local purchases from family farmers creates markets and helps to improve the quality and supply of food, said the Director-General.

This is also vital for building resilience and strengthening livelihoods by disseminating information on income generation opportunities, in particular to empower poor women. It is something that can be done relatively simply through the use of mobile telephones, working with the private sector in the development of mobile phone apps that provide market information.

The post G7 countries can help farmers access data for building resilience appeared first on The Source.

]]>The post Why measure? Introducing the Water Indicator Application appeared first on The Source.

]]>Our daily life is full of indicators: from GDP providing an indication of economic health, to grades in school to show how a student has performed, to body temperature confirming whether or not a patient has a fever. But, what are indicators and why are they important?

Indicators are a measurement or value that gives you an idea of what something is like. They help us to track the development of statuses, projects or even sicknesses. Indicators help us to see and understand if a situation is improving or getting worse.

Indicators applied in water resources help us to understand a wide variety of quality and quantity challenges. They are also fundamental to helping understand changes brought about to the water cycle by climate change. In the water world, indicators allow us to observe and understand the situation of water quality, rainfall, floods and droughts, and can help establish a basin-wide view of how we should respond.

Measuring these parameters, however, can be very complicated. Take, for example, tracking the beginning and end of a drought. Information about rainfall alone is not always enough to determine the length of a drought or its severity. There are many indicators that could be used to assess drought, and those choices are part of the problem. How do we know which ones would be best applied to understand our specific situation? How do we use the assessment to provide more comprehensible information on a drought?

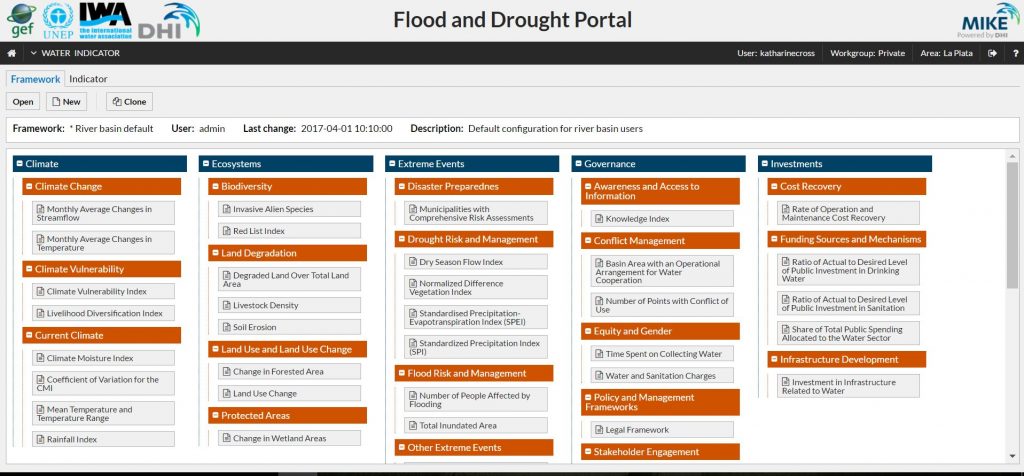

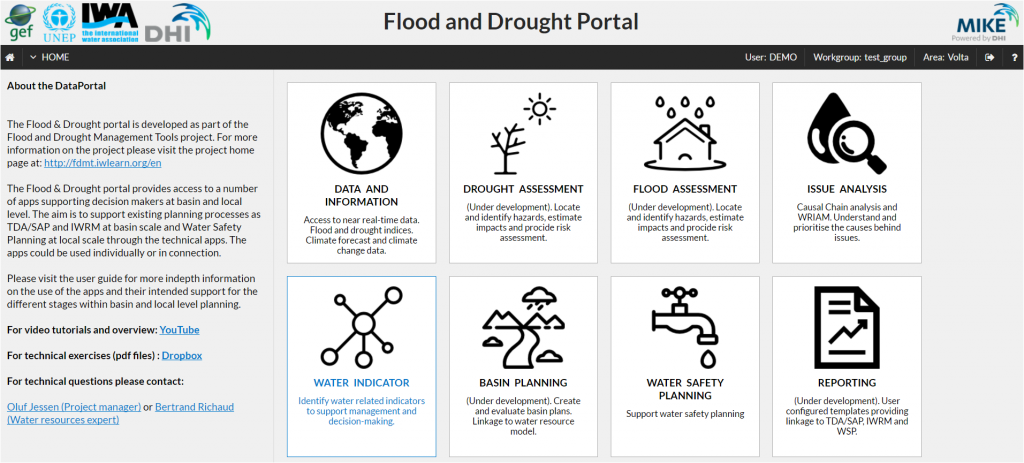

The Flood and Drought Management Tools project is looking at ways to address these concerns. The project has developed the Water Indicator Application, which offers a good starting point to identify the right indicators to assess a particular situation. The application has a default framework that can easily be adjusted to different needs, providing us with the best set of indicators for an organisation or project. Each indicator comes with an explanation of how it can be applied and the data required for an assessment. The application is also a learning tool for basin organisations and other users.

The Water Indicator Application opens up new possibilities for different users from basin organisations, to civil society, to utilities. The Application is practical for creating a framework to guide performance improvement in managing water resources, and understanding the full range of possibilities is beneficial for water utilities. This is true of drought indicators and rainfall indicators, both of which could be relevant for the creation of new risk management programs.

A growing concern for utilities is the disruption of supply due to water scarcity and drought. In order to monitor the situation the utility needs to know what to measure, what information is being provided, and how to use it to better understand and manage water resources. The Water Indicator Application provides us with new opportunities for the mitigation of future droughts and floods. This is critical as uncertainty in climate variability grows and the impacts of climate change are felt more severely on water security.

The Water Indicator Application is accessible at www.flooddroughtmonitor.com, and the Application is accessible for all registered users of the Flood and Drought portal, which is targeted at decision makers at the basin and local level to support their planning processes. You can find further instructions here.

About the Flood and Drought Management Tools project

The Flood and Drought Management Tools (FDMT) project is funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) International Waters (IW) and implemented by UN Environment (UNEP), with DHI and the International Water Association (IWA) as the executing agencies. This project is developing online technical applications to support planning from the transboundary basin to water utility level by including better information on floods and droughts. The project is being implemented from 2014–2018, with 3 pilot basins (Volta, Lake Victoria and Chao Phraya) participating in development and testing of the methodology and technical applications.

The post Why measure? Introducing the Water Indicator Application appeared first on The Source.

]]>